Practical Optics Selection For the Tactical Shooter

By Ian Kenney

For many long range shooters, hobbyists and enthusiasts alike, a riflescope is probably one of the bigger purchases that they’ll make when finishing a new rifle build or simply upgrading scopes. I’ve been there quite a few times myself and have experienced what the effect of having a lot of choices on hand can do to the decision making process. In this article I’m going to go through the criteria that I use when looking for a new scope and hope that you can apply some of the same thinking to your next optics purchase.

The criteria that I use when selecting an optic are:

· Intended Use

· Budget

· Features

· Reliability

· Company Support

· Accessory Availability and Compatibility

Intended Use

The first thing that has to be done when selecting a new optic is determine exactly what the shooter intends to do with the rifle that the scope will be attached to. When examining the intended use of the optic the shooter should take things into account such as the average size of the targets they will be engaging, the average distance for shots, and the conditions that they’ll likely be shooting in. It’s these things that can help drive the other factors, such as the allowable budget and scope features, in order to select the right optic. For example, a rifle that will be used well within 200 yards 90% of the time will have different optics requirements compared to a similar rifle that will be used for targets that are in excess 500 yards 70% of the time. The average conditions that a shooter will use a scope in can also help to select the right one since they may not need one with all of the advanced features if it is only going to be taken out once a month on a pretty day to best their smallest group size. Figuring out what I plan to do with something will allow me to look in the right direction and not waste as much time by looking at all the other options.

Budget

After figuring out what the intended use for the riflescope is going to be, the next thing to determine is how much is the shooter willing to spend on it? This is a big deciding factor for many people and it’s important to get the best riflescope that you can afford that has the features and qualities that you are looking for. In some cases that may mean making some compromises in regards to available features such as an illuminated reticle or zero stop features. However, there are some manufacturers that make different lines of scopes that can fit the needs and budgets of a wide variety of shooters that often provide similar features and performance.

Features

Choosing the right riflescope for the application often means choosing one that has the right combination of features even if some compromises have to be made in other areas. However, it seems that many shooters will compromise features for optical performance when this particular characteristic really isn’t the most important one to look at. Here are some features that I feel are important to consider when selecting a new riflescope:

· Magnification Range

· First Focal Plane or Second Focal Plane Reticles

· The Reticle

· Matching Knobs and Reticles

· Elevation and Windage Knob Styles

· Internal Elevation Travel

· Eye Relief

· Parallax Adjustment

Magnification Range

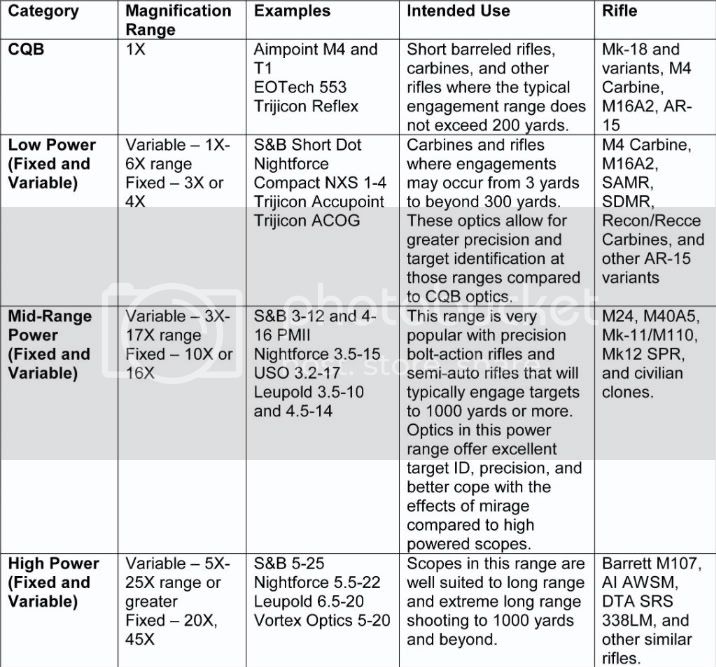

Choosing a scope with the proper magnification range goes back, in part, to the intended use fo the rifle and the user's personal prefernces. The inteneded use of the rifle will generally steer the shooter to a certain style of optic or range of magnification but the user's preferences will make the final decision. I like to group the magnification range of optics in to four categories:

There are some considerations that have to be taken into account though when selecting the proper magnification range. One of those is, of course, the size of the target that the shooter will most likely be engaging and generally I’ve found that the smaller the targets get the more it helps if to have the magnification level go up too. However, selecting a high magnification optic also comes with some considerations of its own such as the effects of mirage and the field of view. Mirage is the distortion of light by alternating layers of hot and cold air, which can be the bane of a long-range shooter’s existence and his little helper all rolled into one. The higher the magnification range goes the more pronounced the effects of mirage are, which are distorted or obscured images of distant targets. I’ve seen IPSC-sized targets reduced to nothing by white blobs at 800 yards because of the effects of mirage. As you can imagine this will greatly hinder the ability of the shooter to accurately hold off for wind or elevation corrections.

Another consideration that should be taken into account when selecting an optic is the field of view, which is what the shooter can see through the optic from one edge to the other at a given magnification setting. I believe there are some exceptions but in general if there are two scopes with equal objective lens sizes the optic with a higher magnification will have the smaller field of view. Why does this matter? Well if the shooter is shooting benchrest competition or simply shooting steel at a fixed distance then having a small field of view doesn’t matter all that much. However, the shooter is engaging moving targets or targets that are at multiple distances then having a larger field of view will help to keep them from getting “lost†while following a target and/or searching for the next one.

Variable powered optics sort of help to mitigate these issues, especially those with higher magnification ranges, since the user can select a lower power that provides an adequate field of view and copes with mirage. The considerations above are why fixed ten-power optics were popular with military and law enforcement shooters for many years. The ten-power magnification was considered adequate enough for target ID, tracking moving targets, and reducing the effects of mirage. However, times have changed and better variable powered optics are on the market that allow the shooter to cope with these issue with relative ease.

First Focal Plane and Second Focal Plane Reticles (FFP and SFP)

The term FFP and SFP refers to the position of the reticle inside of the scope which can be very important depending on the type of scope and it’s intended use. FFP scopes have the reticle located at the front of the erector, which means that the subtension of the reticle does not change from high to low power. For tactical shooters this means that the reticle can be used on any power to shoot at targets on the move, compensate for trajectory, or estimate the range to a target. Since the reticle is accurate at any power within the magnification range the shooter has one less thing to worry about under high stress situations. The only apparent downside to FFP reticles is that on the lowest power setting the reticle will be too small to effectively use the graduations on the reticle. Of course if the scope is dialed down to 3X or 4X chances are it’s not to get a range on something.

SFP scopes have their reticles placed towards the rear of the erector and are a very common arrangement with riflescopes here in the States. This means that when the shooter goes from high to low magnification the reticle will appear to remain the same size in relation to the shooter. This also means that the reticle is accurate at only one power, which may or may not be the highest magnification setting. With some practice, the reticle can be used on other, intermediate magnifications, but it is not as intuitive as using a FFP reticle. Scopes with SFP reticles are a good choice if the shooter is only target shooting on a “square†range or for a general hunting-type application where using the scope for trajectory compensation at intermediate power settings is not needed.

The Reticle

There are a plethora of reticles available on the market with many manufacturers offering several reticle options for one model of scope. It is important though that the reticle chosen will adequately meet the needs of the shooter and their intended use. Long-range tactical shooters often prefer a mil-based or MOA reticle over the more basic duplex reticle since it offers more than just an aiming point for engaging targets. Reticles suitable for long-range should be graduated with dots and/or hash marks to give the shooter additional reference points when estimating range and compensating for trajectory. That being said the typical target shooter or varmint hunter may not need all of those graduations and might prefer a simple thin crosshair with or without a center dot aiming point. Again it all goes back to the intended use of the rifle and the scope.

Bullet Drop Compensation (BDC) reticles seem to be most popular with low-powered fixed and variable powered optics, however they are also finding their way into some mid-range powered scopes. BDC reticles, like the one in the TA31F and Burris XTR 1-4, shine in situations where the shooter’s concern is getting rounds downrange quickly and relatively accurately. The most common issue with BDC reticles though is that they are often designed around a specific cartridge in a specific set of conditions. The ammunition and conditions the reticles are based around are typically quite different from what the shooter may actually experience so it requires the shooter to confirm their hold over points on the reticle at various distances. Some companies have made semi-generic BDC reticles, like the Nikon BDC 600 reticle and Nightforce Velocity Reticle, that can be tuned to a specific cartridge with the use of a ballistic program that gives the shooter both speed and accuracy from the reticle.

Whichever type of reticle is chosen though it should fit the needs of the shooter and the situations that they’ll typically find themselves in. A reticle that was designed for the F-class field suddenly starts getting used for tactical rifle competitions the shooter may find that it is too thin and will easily get lost in vegetation and changing light.

Matching Reticle and Click Values

In the optics industry, one of the greatest evolutions in recent years is the development of affordable optics that have click values on the elevation and windage knob that match the reticle inside of the scope. For many serious tactical shooters matching the click values on the turret to the reticle inside of the scope is a big determining factor when selecting a riflescope. For many years though this feature was once only available on scopes that cost thousands of dollars and came from far away lands. However, in just the past couple of years scopes from Bushnell, SWFA, Millet have come out with scopes that have mil-based reticles and 0.1 mrad knobs, all for well under $1,000. For those that don’t know, using a scope that has a matching reticle and click values lets the shooter make faster corrections and adjustments since what he sees through the scope are the corrections that he has to make on the knob. Optics with mismatched reticles and click values require the shooter to convert what he sees through the scope into an elevation or windage correction, which increases the chances for an error. Having a scope with matching adjustments and reticles also makes it a little easier for beginners since they won’t have to worry about any kind of conversion going from Mil to MOA or vice versa. Modern ballistics programs are also making it easier for a person to work in all Mils or all MOA increasing the user friendliness.

Elevation and Windage Knobs

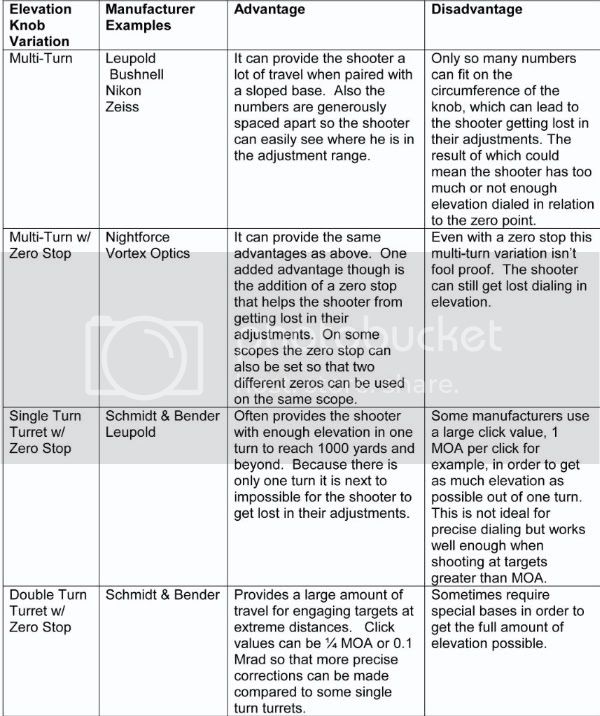

When selecting a riflescope not much thought is usually given to the elevation and windage knobs and the features they can offer the shooter. Elevation and windage knobs come in a variety of forms from simple covered, hunter-style turrets to exposed tactical knobs with zero stops and other features. Riflescopes that are best suited to precision bolt-action and semi-auto rifles should at least have exposed tactical or target-type turrets that can be reset to “0†once the rifle has been sighted in. These exposed, tactical turrets come in many variations such as multi-turn, multi-turn with zero stop, as well as single and double turn knobs with zero stops. Many manufacturers also offer additional features such revolution indicators and more tactile clicks that help the shooter keep track of adjustments in low light situations. Below is a chart that lists some of the advantages and disadvantages among some of the elevation and windage knob variations.

Optics that utilize BDC reticles don’t really require exposed knobs or ones that can be reset since the reticle, not the knobs, are most often used for trajectory compensation. These scopes often have simple, covered elevation and windage knobs that are pretty much only used for zeroing the scope at the desired range.

The Zero Stop

A zero stop is a system that some manufacturers use to keep the shooter from going past a certain point in the travel range to keep the shooter from getting “lost†while turning the knob. A zero stop can be a very important feature for the shooter that will use the scope in tactical, high stress situations since it allows them to easily reset the knob if they are not sure how much elevation they’ve really dialed into the scope. It’s a gut wrenching feeling to start cranking back on the elevation knob after having made a shot and not know exactly how much dope you dialed in or where your zero point is. Zero stops come in all shapes and sizes today with some simply being a series of stackable bushings to clutch mechanisms. Additionally, even though the name for this feature is “zero stop†the actual point at which the knob stops isn’t always right on the zero point. Depending on the manufacturer and/or model of the scope, the point at which the zero stops can be right on the zero, several clicks below, or at a point that can be set by the shooter. This later method is particularly useful since it allows the shooter to zero two different types of ammunition for one rifle without too much trouble.

Some manufacturers also have a kind of zero stop feature for their windage knobs that limits the rotation of the windage to prevent the shooter from coming all the way around. Just like the elevation zero stop, this windage zero stop can be a very handy feature for the tactical shooter that might find themselves in high stress, time sensitive situations. I was at a competition some years back and a friend of mine was using a scope that had a multi-turn windage knob with no stop of any kind. During the course of the match as he removed and inserted the rifle into his back the windage knob would inadvertently turn, throwing his zero off a little each time. Unfortunately he didn’t notice the issue until he took a shot and witnessed the impact almost three mils right of his intended point of impact.

More Tactical Clicks and Revolution Indicators

Two other features that may interest the tactical shooter are More Tactical Clicks and revolution indicators. More Tactile Clicks (MTC) first came on the scene several years ago as the result of a military contract and have been slowly finding their way into other manufacturer’s optics. The MTC knob uses a distinctive “clunk†every full mil compared to the other “clicks†while the knob is turned so the shooter has an audible and tactile reference for the amount of travel they’ve dialed in. This allows them to dial the correct amount of elevation without even looking or in complete darkness. For example if the shooter has to dial in 4.2 mils of elevation all they need to do is to quickly dial Clunk, Clunk, Clunk, Clunk, and click, click to reach 4.2 mils.

Revolution indicators are another handy feature for scopes that have MTC knobs and/or knobs that can have multiple revolutions. Revolution indicators come in many guises, such as simple lines on the elevation assembly or as more complicated windows and protruding surfaces. The more simple lines on the elevation assembly are found on multi-turn elevation knobs from Leupold, Vortex Optics, and Zeiss/Hensoldt. The more complicated revolution indicators can be found on Schmidt & Bender PMII optics that have either standard double turn knobs or the MTC double turn knobs. On the S&B standard double turn knob, when the shooter begins to go into their second revolution, a series of clear windows on top of the knob will begin to turn yellow. When the windows become fully yellow the shooter now has a visual indication that they are in the second revolution of the elevation knob. Likewise, if the scope is equipped with a MTC knob, a round “donut†will begin to elevate as the shooter goes into the second revolution. This “donut†gives the shooter another tactile reference, in addition to the MTC feature, so that can make full adjustments without looking at the knob itself or in the dark.

Internal Elevation Travel

When selecting a riflescope it’s important to look at the specifications provided by the manufacturer and in particular the amount of internal elevation travel that is listed for the scope. The manufacturer usually lists the total internal travel as 50 MOA, 65 MOA, 90 MOA, etc…in the specifications and this is the amount of travel the erector has from stop to stop inside the scope. Some shooters mistakenly think that this number given by the manufacturer as “Total or Max Elevation adjustment means that this is the amount of travel they have once they zero. This is rarely the case since when a scope arrives from the manufacturer, the erector is centered within the tube to provide the shooter the maximum amount of travel in order to zero. So if a scope is listed as having 100 MOA of elevation travel, which is generous for a tactical riflescope, it should have 50 MOA up and down. The total amount of internal travel is important because it can help the shooter select not only the right scope for the application but also further guide them when selecting the proper mounting solution so that the scope can be used to its full potential. It is important to keep in mind though that generally the higher the magnification a scope has, the less internal travel it will have also. This lack of elevation will sometimes require a sloped base in order for the scope to function properly and reach the distances that the shooter desires. Whether an optic has 100 MOA of internal travel or 50 MOA, I consider it a good idea for the shooter to at least get a 20 MOA base to mitigate the chances of not having enough elevation travel.

To understand more about how the base and rings interact with the riflescope please go here!

Eye Relief

Another specification that I pay close attention to when selecting a riflescope is the amount of eye relief given for the scope. Having enough eye relief can mean all the difference in the world if you are shooting a magnum caliber rifle. For long-range bolt action and some semi-auto rifles the eye relief should provide sufficient space between the ocular lens and the eye, with 3†â€" 3.5†on high power being pretty common. It is also important with variable powered optics that the change in eye relief be minimal from high to low power. This means that the cheek weld can be more consistent when using the scope at various settings and in various positions. Some optics such as the 4X Trijicon ACOG has a shorter eye relief compared to other riflescopes since it has only 1.5†of eye relief. This is fine for soft recoiling rifles such as the AR-15 but on harder recoiling rifles this can become a painful issue. The amount of eye relief is also important when mounting a scope since the optic should be positioned so that when the shooter has a full field of view when positioned comfortably behind the rifle. Sometimes this requires a special mount or base but it really just depends on the rifle and optic set up.

Parallax Adjustment

Parallax is the apparent movement of the reticle against the target image caused by the target and reticle not being focused onto the same image plane. If a scope is not parallax free then the reticle will appear to “dance†around the target if the shooter looks through the scope and moves their head without touching the stock. Having a parallax free image means that the reticle will not move off of the point of aim no matter what the position of the shooter’s head is. Compensating for the effects of parallax becomes an important issue as the distance to targets increases and the magnification levels go up. There are typically two ways that manufacturers compensate the effects of parallax, either they use an adjustable objective or a side-focus knob. Each method is different in how they move the internal lenses to bring the target image and reticle into the same focal plane but they all achieve the same goal. The side focus knob can be easier for some to manipulate when in a shooting position while others seem to find the adjustable objective more forgiving if the dial isn’t in the perfect place. There are some scopes though, both fixed and variable powered models that have a fixed parallax setting, usually somewhere between 100 and 300 yards/meters. Having a fixed parallax setting means that at one specific distance the target image and reticle are on the same image plane. However I’ve found that the scopes with fixed parallax settings tend to have a lower magnification level, typically below 10X, since the effects of parallax won’t be as pronounced. That’s not to say though that parallax has no effect on with these optics if the target falls outside of the parallax free distance and the fundamentals of marksmanship aren’t adhered to.

When I start looking at new scopes I generally like to have some sort of parallax adjustment on anything that is above 12X and that’ll be used at longer ranges. Having some sort of parallax adjustment will allow me to get a nice focused image on higher magnifications and allow my head some wiggle room if I can’t get perfectly behind the rifle in the field. I typically don’t have an issue with a scope if it doesn’t have any means of parallax compensation as long as the maximum magnification level is below 10X. I’ve found that below 10X parallax is definitely present, just not as pronounced as say on a 15X optic and the lower magnification allow for a target image that is still crisp and clear.

Reliability

After looking at what I intend to do with an optic, my budget, and some of the options that are out there I begin to look at the reliability of the riflescope. When I talk about the reliability of an optic I not only mean it’s ability to withstand some abuse but also the accuracy and repeatability of its adjustments. More so than any other quality sought in a tactical riflescope this is the most important, because if you cannot trust the click values and its ability to return to zero after dialing in a lot of elevation then it is practically useless. It’s always a good idea to test the repeatability of the elevation and windage adjustments no matter how much the scope cost or the reputation of the manufacturer.

Company Support

Another important factor in my selection for a new riflescope is to take a look at the company and their standing within the shooting community. While many overlook this aspect, I feel that a product is only as good as the company backing it, no matter how awesome the scope looks on paper. I like to see optics companies that offer no questions asked customer service as well as a variety of options that meet the needs of a variety of shooters. It’s also nice to see companies that are receptive to the requests of their customers as well as their critics in order to help further their product line. Having the newest FFP scope with the best glass and the newest zero stop system means nothing when it breaks and the customer service rep blows you off. Additionally I seem to favor companies that don’t require the scope to be shipped overseas for repairs since that can greatly increase the downtime on a rifle and cause major headaches for the customer. In my experience if a scope stays within the continental United States for repairs then the downtime is usually between two to three weeks instead of two to three months if it has to go overseas.

Accessories

When selecting a riflescope, the last bit of criteria that I look at is the availability and compatibility of accessories and other ancillary equipment. What I mean by that is are mounting solutions for the scope pretty common? Will a special base be needed? Are sunshades and flip caps easily available for the scope? Asking and obtaining the answers to these questions can make life a whole lot easier in the long run for the owner. Otherwise they may end up purchasing a scope that has an odd tube diameter, which only a couple of manufacturers make rings for and it still needs a special base in order to get the proper eye relief.

Red Herrings

As you were going through this article you may have noticed that I made no mention of a scope’s tube and objective diameter, its lens coatings, optical quality or light transmission figures. The truth is these things have little bearing on my decision when I’m choosing an optic and I feel that more often than not they draw the unknowing consumer in the wrong direction; It’s not really evil, it’s just good marketing.

In The End

The above criteria that I have discussed are not the end all be all criteria to use when selecting a riflescope, it is simply a set of guidelines that have worked for me in the past. With some modifications to the criteria these guidelines can be applied across teh board to riflescopes meant for other purposes such as hunting as well as other categories of optics such as spotting scopes. I hope this article has helped to give you a better understanding of some of the things that you should think consider when selecting a riflescope and look beyond most of the marketing hype.

To understand more about how the riflescope works please go here!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Practical Optics Selection for The Tactical Shooter

- Thread starter KillShot

- Start date